In 2010, leading screenwriting guru Linda Aronson gave a talk at the London Screenwriters’ Festival that caused a sensation because it exploded the conventional Hollywood approach to screenwriting. The audience of scriptwriters was so anxious to hear more that they kept Linda talking for almost five hours after the lecture was finished.

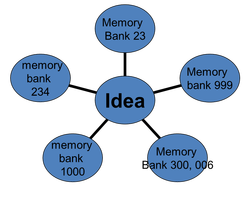

What galvanized the writers were Linda Aronson’s step by step guidelines for planning and writing screenplays like 'Pulp Fiction' or 'The Usual Suspects' that use components like flashbacks, time jumps, multiple protagonists and nonlinear storylines – all elements frowned upon or actively banned by other screenwriting gurus.

In 2011 Linda Aronson came back to the London Screenwriters’ Festival and gave an expanded form of the lecture to hundreds of writers, explaining how to construct eighteen storytelling structures apart from the conventional linear, chronological one-hero model.

That historical, game-changing lecture was filmed by the London Screenwriters' Festival. For the first time it is now made publicly available by Linda Aronson in conjunction with the London Screenwriters' Festival in a special licence permitting you to view and keep on to download and own on three different digital devices. Watch a trailer.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed